Slack’s Security Engineering team is responsible for protecting Slack’s core infrastructure and services. Our security event ingestion pipeline handles billions of events per day from a diverse array of data sources. Reviewing alerts produced by our security detection system is our primary responsibility during on-call shifts.

We’re going to show you how we’re using AI agents to optimize our working efficiency and strengthen Slack’s security defenses. This post is the first in a series that will unpack some of the design choices we’ve made and the many things we’ve learnt along the way.

The Development Process

The Prototype

At the end of May 2025 we had a rudimentary prototype of what would grow into our service. Initially, the service was not much more than a 300 word prompt.

The prompt consisted of five sections:

- Orientation: “You are a security analyst that investigates security alerts […]”

- Manifest: “You have access to the following data sources: […]”

- Methodology: “Your investigation should follow these steps: […] ”

- Formatting: “Produce a markdown report of the investigation: […]”

- Classification: “Choose a response classification from: […]”

We implemented a simple “stdio” mode MCP server to safely expose a subset of our data sources through the tool call interface. We repurposed a coding agent CLI as an execution environment for our prototype.

The performance of our prototype implementation was highly variable: sometimes it would produce excellent, insightful results with an impressive ability to cross-reference evidence across different data sources. However, sometimes it would quickly jump to a convenient or spurious conclusion without adequately questioning its own methods. For the tool to be useful, we needed consistent performance. We needed greater control over the investigation process.

We spent some time trying to refine our prompt, stressing the need to question assumptions, to verify data from multiple sources, and to make use of the complete set of data sources. While we did have some success with this approach, ultimately prompts are just guidelines; they’re not an effective method for achieving fine-grained control.

The Solution

Our solution was to break down the complex investigation process we’d described in the prompt of our prototype into a sequence of model invocations, each with a single, well-defined purpose and output structure. These simple tasks are chained together by our application.

Each task was given a structured output format. Structured output is a feature that can be used to restrict a model to using a specific output format defined by a JSON schema. The schema is applied to the last output from the model invocation. Using structured outputs isn’t “free”; if the output format is too complicated for the model, the execution can fail. Structured outputs are also subject to the usual problems of cheating and hallucination.

In our initial prototype, we included guidance to “question your evidence”, but had mixed success. With our structured output approach, that guidance had become a separate task in our investigation flow with much more predictable behavior.

This approach gave us more precise control at each step of the investigation process.

From Prototype to Production

While reviewing the literature, two papers particularly influenced our thinking:

- Meta-Prompting: Enhancing Language Models with Task-Agnostic Scaffolding (Stanford, OpenAI)

- Unleashing the Emergent Cognitive Synergy in Large Language Models: A Task-Solving Agent through Multi-Persona Self-Collaboration (Microsoft Research)

These papers describe prompting techniques that introduce multiple personas in the context of a single model invocation. The idea of modelling the investigation using defined personas was intriguing, but in order to maintain control we needed to represent our personas as independent model invocations. Security tabletop exercises, and how we might adapt their conventions to our application, were also a major source of inspiration during the design process.

Our chosen design is built around a team of personas (agents) and the tasks they can perform in the investigation process. Each agent/task pair is modelled with a carefully defined structured output, and our application orchestrates the model invocations, propagating just the right context at each stage.

Investigation Loop

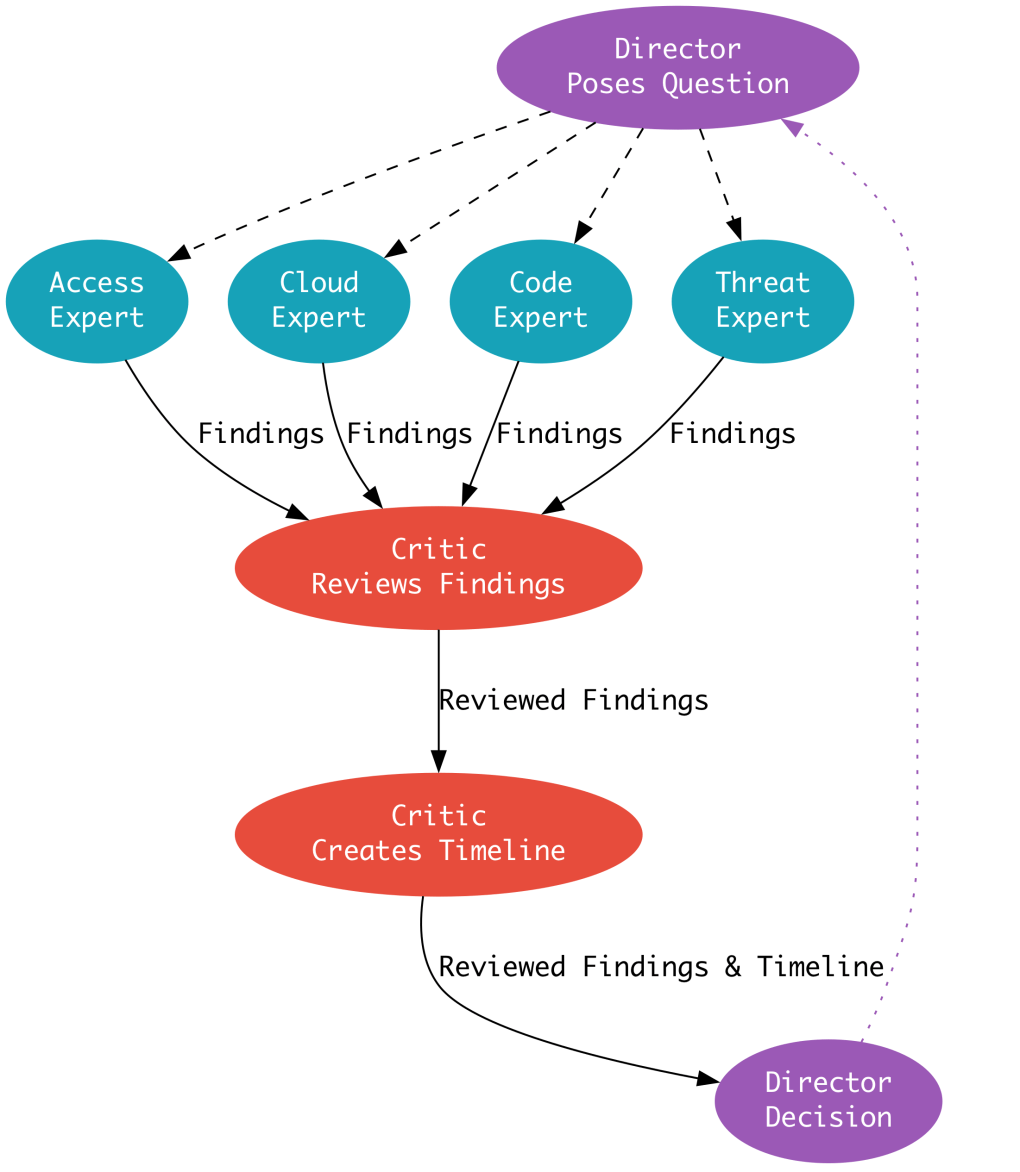

Our design has three defined persona categories:

Director Agent

The Investigation Director. The Director’s responsibility is to progress the investigation from start to finish. The Director interrogates the experts by forming a question, or set of questions, which become the expert’s prompt. The Director uses a journaling tool for planning and organizing the investigation as it progresses.

Expert Agent

A domain expert. Each domain expert has a unique set of domain knowledge and data sources. The experts’ responsibility is to produce findings from their data sources in response to the Director’s questions.

We currently have four experts in our team:

-

- Access: Authentication, authorization and perimeter services.

- Cloud: Infrastructure, compute, orchestration, and networking.

- Code: Analysis of source code and configuration management.

- Threat: Threat analysis and intelligence data sources.

Critic Agent

The Critic is a “meta-expert”. The Critic’s responsibility is to assess and quantify the quality of findings made by domain experts using a rubric we’ve defined. The Critic annotates the experts’ findings with its own analysis and a credibility score for each finding. The Critic’s conclusions are passed back to the Director, closing the loop. The weakly adversarial relationship between the Critic and the expert group helps to mitigate against hallucinations and variability in the interpretation of evidence.

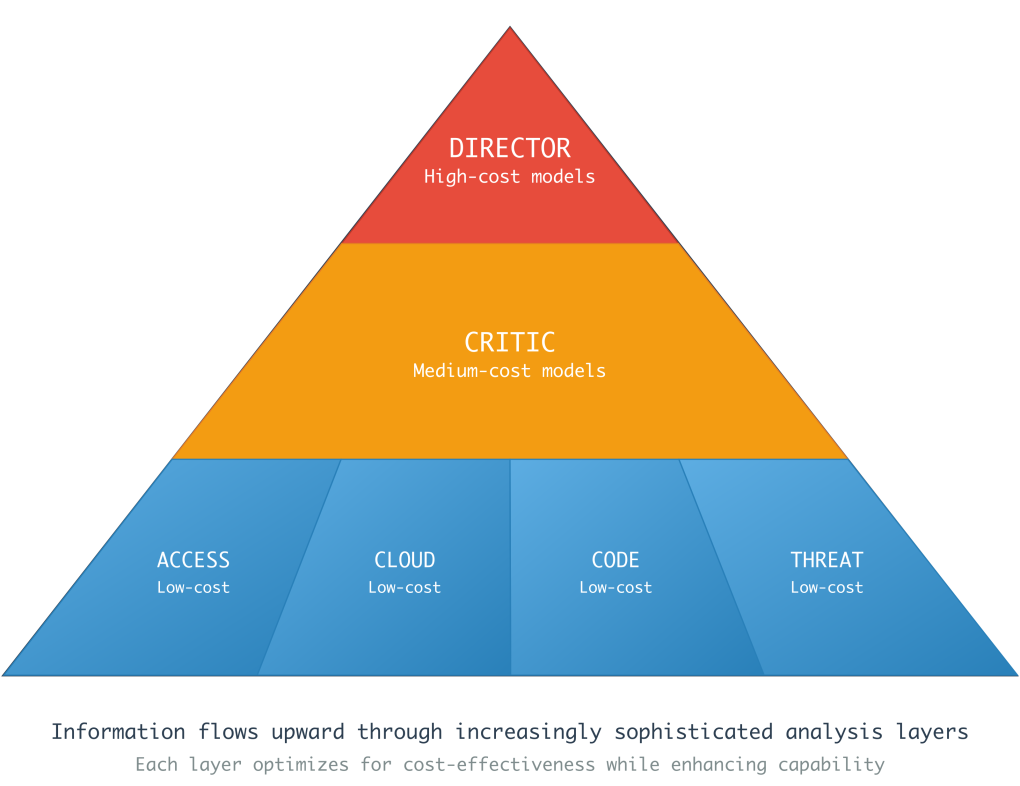

Because each agent/task pair is a separate model invocation we can vary all of the inputs, including the model version, output format, prompts, instructions, and tools. One of many ways we’re using this capability is to create a “knowledge pyramid”.

Knowledge Pyramid

At the bottom of the knowledge pyramid, domain experts generate investigation findings by interrogating complex data sources, requiring many tool calls. Analyzing the returned data can be very token-intensive. Next, the Critic’s review identifies the most interesting findings from that set. During the review process the Critic inspects the experts’ claims and the tool calls and tool results used to support them, which also incurs a significant token overhead. Once the Critic has completed its review, it assembles an up to date investigation timeline, integrating the running investigation timeline and newly gathered findings into a coherent narrative. The condensed timeline, consisting only of the most credible findings, is then passed back to the Director. This design allows us to strategically use low, medium, and high-cost models for the expert, critic, and director functions, respectively.

Investigation Flow

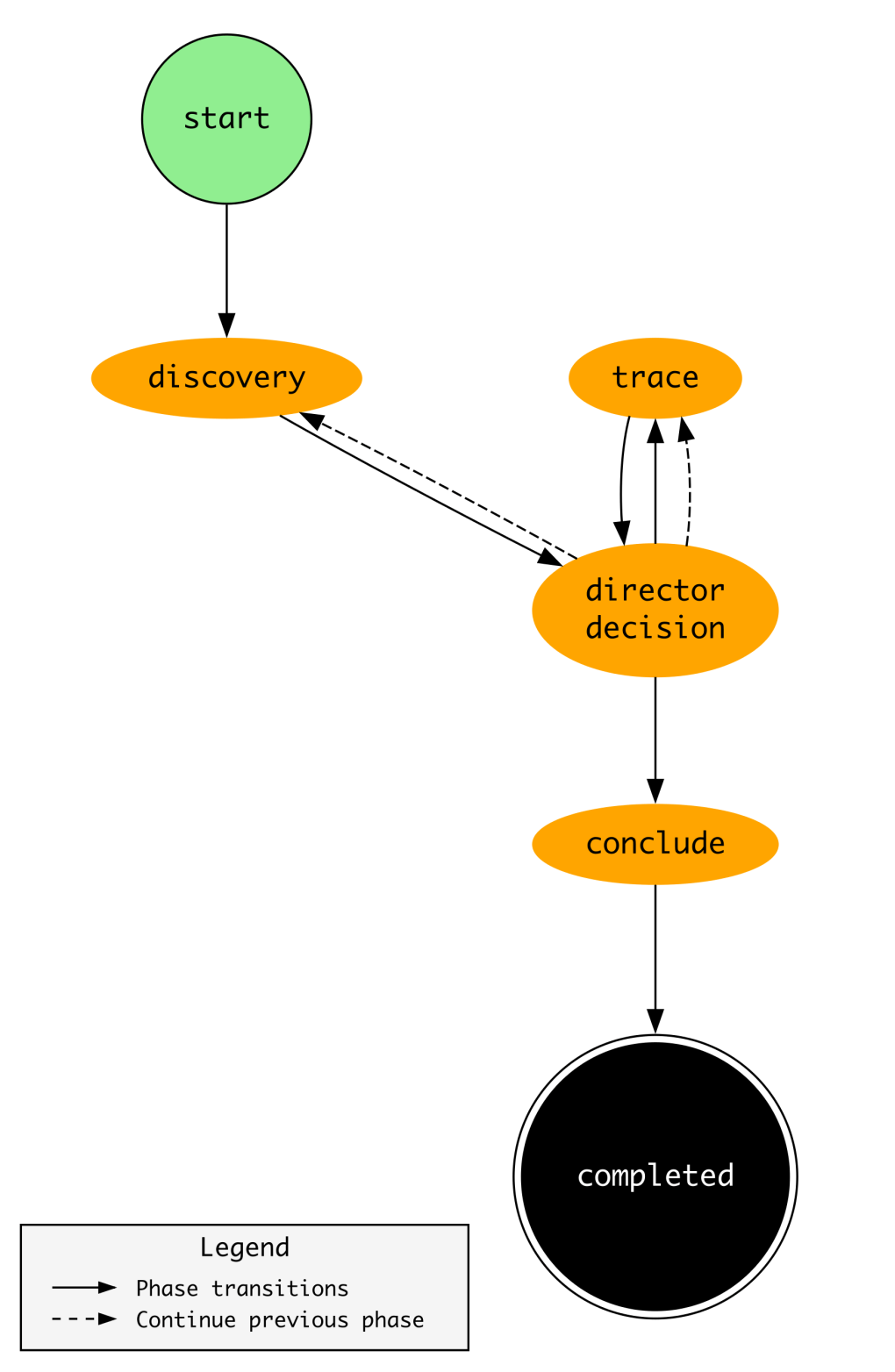

The investigation process is broken into several phases. Phases allow us to vary the structure of the investigation loop as the investigation proceeds. At the moment, we have three phases, but it is simple to add more. The Director persona is responsible for advancing the phase.

Discovery

The first phase of each investigation. The goal in the discovery phase is to ensure that every available data source is examined. The Director reviews the state of the investigation and generates a question that is broadcast to the entire expert team.

Director Decision

A “meta-phase” in which the Director decides whether to advance to the next investigation phase or continue in the current one. The task’s prompt includes advice on when to advance to each phase.

Trace

Once the discovery phase has made clear which experts are able to produce relevant findings, the Director transitions the investigation to the trace phase. In the trace phase, the Director chooses a specific expert to question. We also have the flexibility to vary the model invocation parameters by phase, allowing us to use a different model or enhanced token budget.

Conclude

The Director transitions the investigation to the concluding phase when sufficient information has been gathered to produce the final report.

Service Architecture

Our prototype used a coding agent CLI as an execution harness, but that wasn’t suitable for a practical implementation. We needed an interface that would let us observe investigations occurring in realtime, view and share past investigations, and launch ad-hoc investigations. Critically, we needed a way of integrating the system into our existing stack, allowing investigations to be triggered by our existing detection tools. The service architecture we created does all of these things and is quite simple.

Hub

The hub provides the service API and an interface to persistent storage. Besides the usual CRUD-like API, the hub also provides a metrics endpoint so we can visualise system activity, token usage, and manage cost.

Worker

Investigation workers pick up queued investigation tasks from the API. Investigations produce an event stream which is streamed back to the hub through the API. Workers can be scaled to increase throughput as needed.

Dashboard

The Dashboard is used by staff to interact with the service. Running investigations can be observed in real-time, consuming the event stream from the hub. Additionally the dashboard provides management tools, letting us view the details of each model invocation. This capability is invaluable when debugging the system.

Example Report

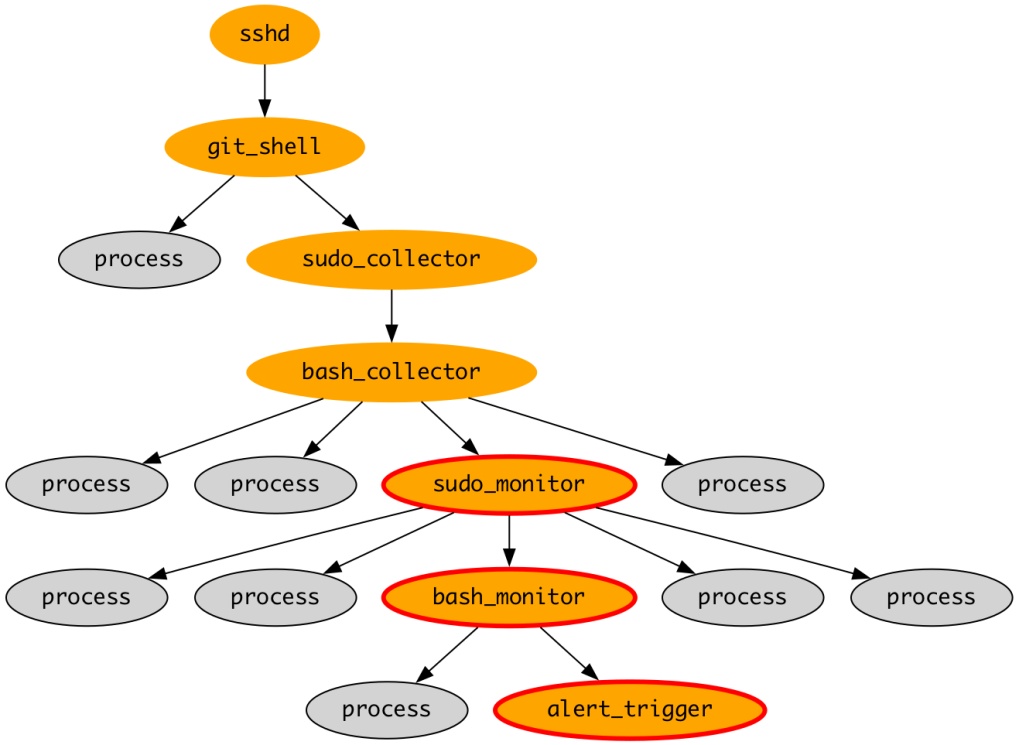

We’ve included an edited investigation report which demonstrates the potential of the agents to exhibit novel emergent behavior. In this case, the original alert was raised for a specific command sequence, which we analyze because it can be an indicator of compromise. In the course of investigating the alert, the agents independently discovered a separate credential exposure elsewhere in the process ancestry.

The text below is a lightly edited version of the report summary from this investigation.

Investigation Report: Credential Exposure in Monitoring Workflow [ESCALATE]

Summary: While investigating [command sequence], the investigation uncovered a credential exposure elsewhere in the process ancestry chain.

Analysis

The investigation confirmed that the command execution on [TIMESTAMP] was part of a legitimate monitoring workflow using [diagnostic tool]. The process ancestry shows the expected execution chain. However, critical security concerns were identified:

- Credential Exposure: A credential was exposed in process command line parameters within the ancestry chain, creating significant security risk.

- Expert-Critic Contradiction: The expert incorrectly assessed credential handling as secure while the critic correctly identified exposed credentials, indicating analysis blind spots that require attention.

What is notable about this result is that the expert did not raise the credential exposure in its findings; the Critic noticed it as part of its meta-analysis of the expert’s work. The Director then chose to pivot the investigation to focus on this issue instead. In the report, the Director highlights both the need to mitigate the security issue, and to follow-up on the expert’s failure to properly identify the risk. We referred the credential exposure to the service owning team to resolve.

Conclusion

We’re still at an early phase of our journey to streamline security investigations using AI agents, but we’re starting to see meaningful benefits. Our web-based dashboard allows us to launch and watch investigations in real time, and investigations yield interactive, verifiable reports that show how evidence was collected, interpreted, and judged. During our on-call shifts, we’re switching to supervising investigation teams, rather than doing the laborious work of gathering evidence. Unlike static detection rules, our agents often make spontaneous and unprompted discoveries, as we demonstrated in our example report. We’ve seen this occur many times, from highlighting weakness in IAM policies, to identifying problematic code and more.

There’s a great deal more to say. We look forward to sharing more details of how our system works in future blog posts. As a preview of some future content from the series:

- Maintaining alignment and orientation during multi-persona investigations

- Using artifacts as a communication channel between investigation participants

- Human in the loop: human / agent collaboration in security investigations

Acknowledgements

We wanted to give a shout out to all the people that have contributed to this journey:

- Chris Smith

- Abhi Rathod

- Dave Russell

- Nate Reeves

Interested in taking on interesting projects, making people’s work lives easier, or just building some pretty cool forms? We’re hiring! 💼

Apply now